2024-02-23

This page outlines the mathematical models of our research project, aimed at comprehensively understanding and predicting the behavior and antibacterial effects of engineered Escherichia coli in simulated gut environments, from the molecular level to community ecological dynamics, through a series of model components.。

The models implemented in this project achieve comprehensive simulation from molecular mechanisms to macroscopic molecular diffusion and population growth. They demonstrate the feasibility of the design pathway and foreshadow the far-reaching impacts of our research.

Our project’s models consist of the following four main components:

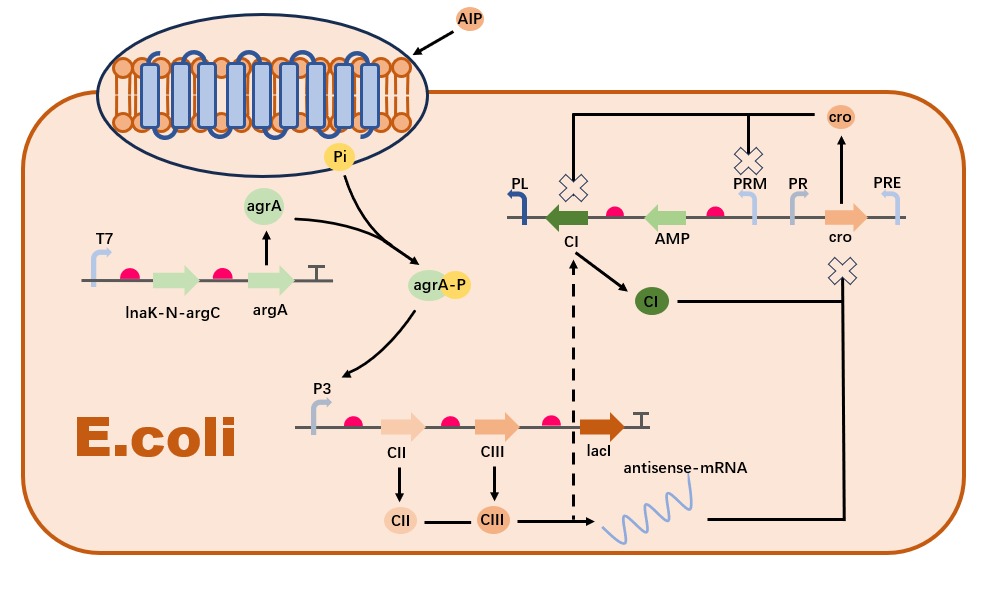

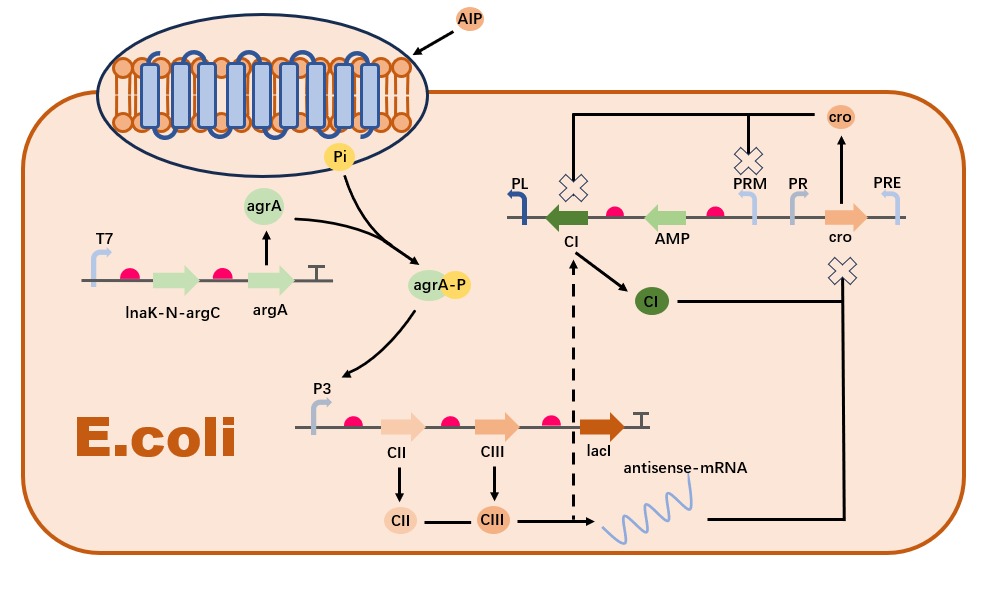

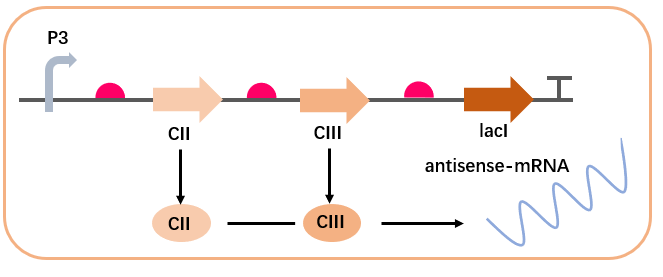

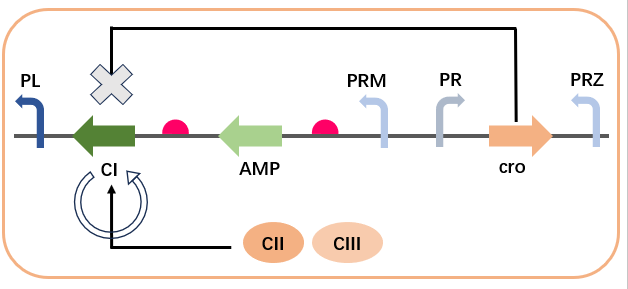

Firstly, we designed a gene regulatory network based on AIP (Autoinducing Peptide) to sense the concentration of Staphylococcus aureus in the environment and regulate the expression of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) in Escherichia coli. This network consists of four main regulatory circuits: a positive feedback loop where AIP activates the expression of CII and CIII proteins, a negative feedback loop where CI and antisense mRNA inhibit the expression of Cro protein, a self-regulating loop of CI, and a cross-regulatory loop where CII, CIII, and Cro inhibit the expression of CI.

In the second part, we applied the Generalized Lotka-Volterra (GLV) model to describe and analyze the competition, predation, and symbiotic relationships among microbial populations in the gut. This model relies on experimental data to determine the relative abundance of different colonies under co-cultivation and employs parameter estimation to quantify the interactions between Escherichia coli and other microbes.。

The third part introduces the simulation of the generation, diffusion, and decay processes of signaling molecules (AIP, AHL, and AMP) in microbial communities. Based on Escherichia coli’s response to AIP concentration thresholds, this section simulates the diffusion dynamics of various molecules in complex environments to better understand the behavior of microbial communities.

Finally, we combined the diffusion Fisher-Kolmogorov equation and the Monod equation to simulate the self-replication and migration processes of populations, taking into account the limitations of nutrient availability on bacterial growth. The Generalized Lotka-Volterra (GLV) model was extended to include population growth processes, while also considering the biofilm synthesis process driven by colonizing bacteria.

In our model, we assume that all protein-protein interactions and protein binding to promoters exhibit switch-like or ultrasensitive characteristics. For example, the binding of a protein to a DNA binding site increases the affinity for a second protein to bind at an adjacent site.

We use a Hill function to describe this ultrasensitive response as follows:

$$\text{Response} = \frac{[S]^n}{K_d^n + [S]^n}$$

where [S] is the concentration of the stimulus (such as AIP), n is the Hill coefficient representing the cooperativity of the interaction, and Kd is the dissociation constant, i.e., the [S] value at which the response reaches half its maximum. When the Hill coefficient n > 1, the system exhibits ultrasensitivity, meaning the response changes sharply with increasing [S].

For details on the overall circuit, refer to [here](details about the overall circuit).

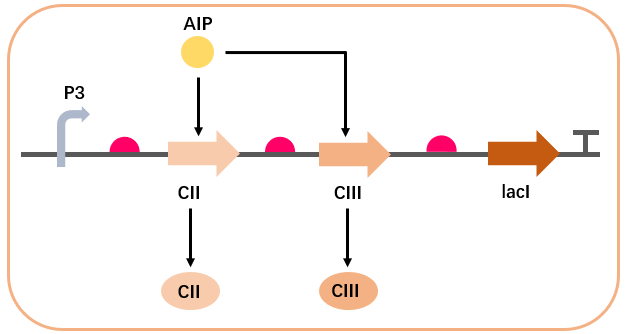

Based on the pathway designed in the Wet Lab, we assume that AIP activates the P3 promoter, thereby promoting the expression of CII and CIII proteins in the AMP synthesis regulatory network. We assume the promoter has a certain baseline activity, and the translation products degrade at a fixed rate. Based on the previously mentioned Hill function model, the dynamics of AIP activation of the P3 promoter can be represented as:

AIP promotes the expression of CII: $$\begin{aligned} \frac{d[CII]}{dt} = & \alpha_{CII} \left( \beta_{0P3} + \frac{(1 - \beta_{0P3}) [AIP]^{n_{aCII}}}{K_{d_{P3CII}}^{n_{aCII}} + [AIP]^{n_{aCII}}} \right) \notag \\ & - d_{CII} [CII] \end{aligned}$$

AIP promotes the expression of CIII: $$\begin{aligned} \frac{d[CIII]}{dt} = & \alpha_{CIII} \left( \beta_{0P3} + \frac{(1 - \beta_{0P3}) [AIP]^{n_{aCIII}}}{K_{d_{P3CIII}}^{n_{aCIII}} + [AIP]^{n_{aCIII}}} \right) \notag \\ & - d_{CIII} [CIII] \end{aligned}$$

In our model, each parameter has the following meanings:

αCII and αCIII represent the maximum rates of CII and CIII protein synthesis, respectively.

β0P3 represents the baseline activity of the P3 promoter in the absence of AIP.

KdP3CII and KdP3CIII are the dissociation constants for the activation of CII and CIII expression by AIP, reflecting the concentration of AIP needed to reach half-maximal expression of CII or CIII.

naCII and naCIII are Hill coefficients describing the cooperativity of AIP in the expression of CII and CIII.

dCII and dCIII are the degradation rates of CII and CIII, respectively.

At equilibrium, $\frac{d[CII]}{dt} = 0$ and $\frac{d[CIII]}{dt} = 0$. Therefore, we can solve for the equilibrium concentrations of CII and CIII.

For CII:

$$0 = \alpha_{CII} \left( \beta_{0P3} + \frac{(1 - \beta_{0P3}) [AIP]^{n_{aCII}}}{K_{d_{P3CII}}^{n_{aCII}} + [AIP]^{n_{aCII}}} \right) - d_{CII} [CII]$$

Solving this equation gives:

$$[CII] = \frac{\alpha_{CII}}{d_{CII}} \left( \beta_{0P3} + \frac{(1 - \beta_{0P3}) [AIP]^{n_{aCII}}}{K_{d_{P3CII}}^{n_{aCII}} + [AIP]^{n_{aCII}}} \right)$$

Similarly, for CIII:

$$[CIII] = \frac{\alpha_{CIII}}{d_{CIII}} \left( \beta_{0P3} + \frac{(1 - \beta_{0P3}) [AIP]^{n_{aCIII}}}{K_{d_{P3CIII}}^{n_{aCIII}} + [AIP]^{n_{aCIII}}} \right)$$

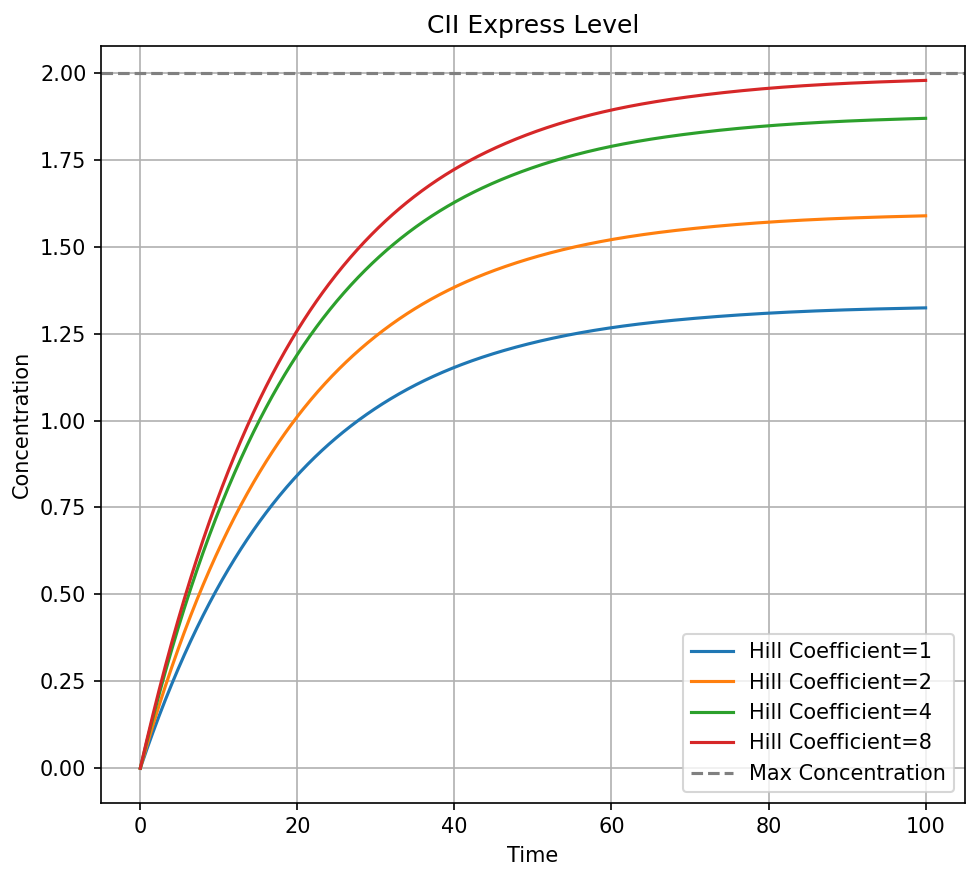

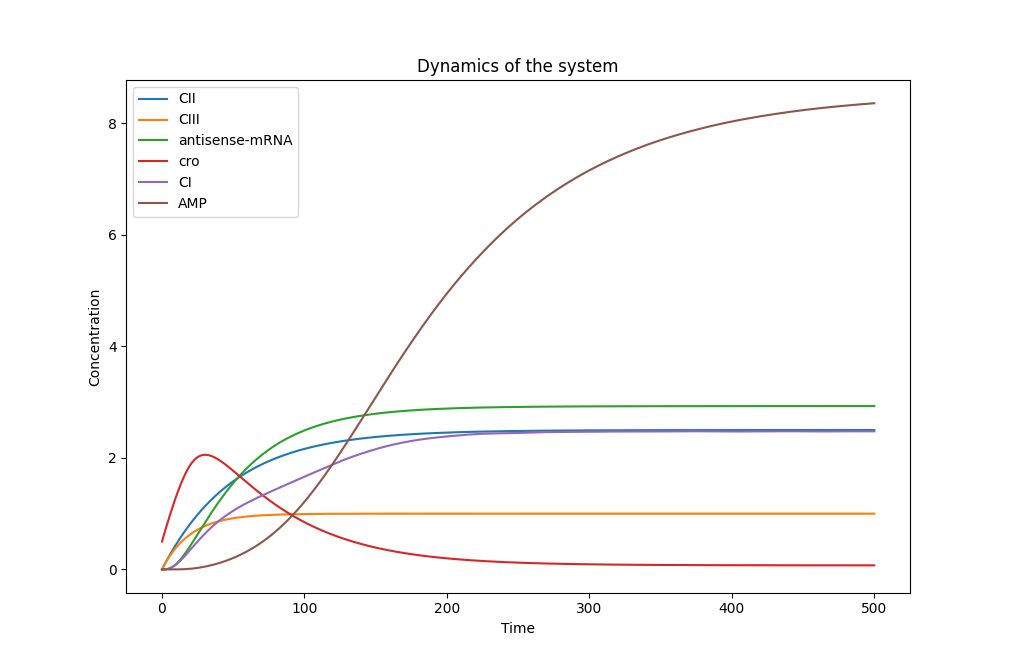

As shown in the figure, the trends of CII and CIII concentrations over time are clearly visible for each Hill coefficient. It can be observed that with time, the concentrations of CII and CIII gradually stabilize, approaching their theoretical maximum values. At extremely high AIP concentrations or relatively high Hill coefficients, it can be assumed that [AIP]naCII ≫ KdP3CIInaCII and [AIP]naCIII ≫ KdP3CIIInaCIII, indicating that the expression of CII and CIII will approach their theoretical maximum values.

The expressions for the maximum concentrations of CII and CIII can be simplified as:

$$[CII]_{max} = \frac{\alpha_{CII}}{d_{CII}}$$

$$[CIII]_{max} = \frac{\alpha_{CIII}}{d_{CIII}}$$

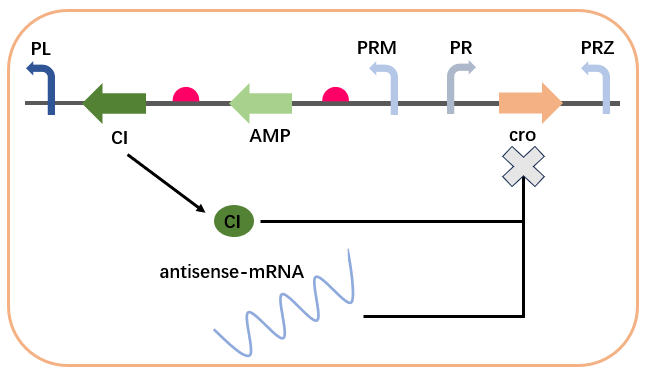

The self-regulation of the CI protein is a crucial component in the AMP synthesis regulatory network. CI protein can bind to its own promoter region, forming a positive or negative feedback mechanism. Specifically, the expression of CI inhibits the transcription of PR, i.e., inhibiting the expression of cro, thereby relieving its own transcriptional inhibition. This leads to rapid accumulation of CI and AMP to high expression levels. However, when the concentration of CI is high (i.e., when AMP reaches high concentrations), CI forms octamers and promotes the formation of DNA loop structures, stabilizing the binding of OL3 and OR3 sites with CI. This inhibits the transcription of the upstream promoter PRM, leading to the suppression of AMP and CI expression, consequently suppressing the concentration of AMP.。

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{d[CI]}{dt} = \alpha_{PRM} \left( \beta_{0PRM} + \frac{(1 - \beta_{0PRM}) [CI]^{n_{aCI}}}{K_{d_{PRMCI}}^{n_{aCI}} + [CI]^{n_{aCI}}} \right) \times \frac{K_{iCI}^{n_{iCI}}}{K_{iCI}^{n_{iCI}} + [CI]^{n_{iCI}}} - d_{CI}[CI] \end{aligned}$$

The meanings of each parameter are as follows:

αPRM represents the maximum rate of CI protein synthesis driven by the PRM promoter.

β0PRM denotes the baseline activity of the PRM promoter in the absence of CI.

KdPRMCI is the dissociation constant for the activation of the PRM promoter by CI.

naCI and niCI are Hill coefficients, representing the cooperativity of CI in activating the PRM promoter at low and high concentrations, respectively.

KiCI represents the factor affecting CI octamer formation and promotion of DNA loop structure formation.

dCI is the degradation rate of CI.

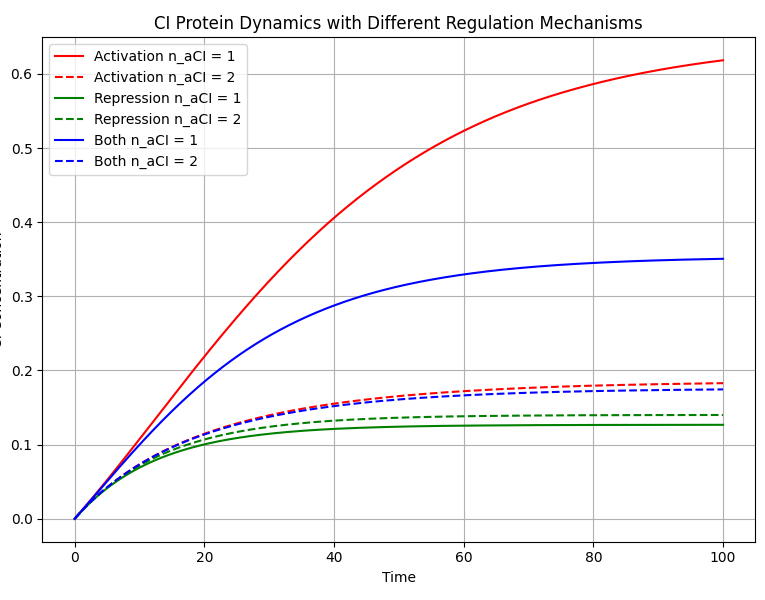

We consider three different self-regulation mechanisms of the CI protein: self-activation, self-inhibition, and their combination. These mechanisms affect the expression level of the CI protein in different ways and can be described by the following differential equations for the change in CI protein concentration [CI] over time t:

$$\frac{d[CI]}{dt} = \begin{cases} \alpha_{\text{PRM}} \left( \beta_{0\text{PRM}} + \frac{(1 - \beta_{0\text{PRM}}) [CI]^{n_{aCI}}}{K_{d_{\text{PRMCI}}}^{n_{aCI}} + [CI]^{n_{aCI}}} \right)\\ - d_{CI} [CI], & \text{if mechanism is "activation"} \\ \alpha_{\text{PRM}} \beta_{0\text{PRM}} \frac{K_{iCI}^{n_{iCI}}}{K_{iCI}^{n_{iCI}} + [CI]^{n_{iCI}}}\\ - d_{CI} [CI], & \text{if mechanism is "repression"} \\ \alpha_{\text{PRM}} \left( \beta_{0\text{PRM}} + \frac{(1 - \beta_{0\text{PRM}}) [CI]^{n_{aCI}}}{K_{d_{\text{PRMCI}}}^{n_{aCI}} + [CI]^{n_{aCI}}} \right)\\ \left( \frac{K_{iCI}^{n_{iCI}}}{K_{iCI}^{n_{iCI}} + [CI]^{n_{iCI}}} \right) - d_{CI} [CI], & \text{if mechanism is "both"} \end{cases}$$

The meanings of each parameter are as follows:

αPRM represents the maximum rate of CI protein synthesis driven by the PRM promoter.

β0PRM denotes the baseline activity of the PRM promoter in the absence of CI.

KdPRMCI is the dissociation constant for the activation of the PRM promoter by CI.

naCI is the Hill coefficient describing the cooperativity of CI in activating the PRM promoter.

KiCI represents the factor affecting CI octamer formation and promotion of DNA loop structure formation.

niCI is the Hill coefficient describing the cooperativity of CI octamer formation.

dCI is the degradation rate of CI.

As shown in the figure, the trends of CI concentration over time are clearly visible for different Hill coefficients and regulatory mechanisms. It can be seen that under different Hill coefficients, our positive and negative feedback self-regulation mechanisms both demonstrate good effectiveness.

The cross-regulation in the AMP synthesis regulatory network involves the regulation of CI expression by CII, CIII, and cro. In the absence of input, the expression of cro inhibits the expression of CI and AMP, reducing the level of gene leakage. Upon input, the CII protein activates the expression of cro’s antisense mRNA chain via PRE, relieving the inhibition on CI, while also expressing CI. CI inhibits the transcription of PR (i.e., the expression of cro), relieving the transcriptional inhibition of cro, allowing CI and AMP to rapidly return to high levels. This complex interaction can be described by the following equations:

CII and CIII promote the expression of antisense mRNA: $$\begin{aligned} \frac{d[\text{antisense-mRNA}]}{dt} = & \alpha_{\text{PRE}} \left( \beta_{0\text{PRE}} + \frac{(1 - \beta_{0\text{PRE}}) ([\text{CII}]^{n_{\text{amRNA}}} + [\text{CIII}]^{n_{\text{amRNA}}})}{K_{d_{\text{PRE}}}^{n_{\text{amRNA}}} + ([\text{CII}]^{n_{\text{amRNA}}} + [\text{CIII}]^{n_{\text{amRNA}}})} \right) \notag \\ & - d_{\text{amRNA}} [\text{antisense-mRNA}] \end{aligned}$$

CI and antisense mRNA inhibited cro expression: $$\begin{aligned} \frac{d[\text{cro}]}{dt} = & \alpha_{\text{PR}} \left( \beta_{0\text{PR}} + \frac{(K_{d_{\text{CI}}})^{n_{\text{CI}}}}{(K_{d_{\text{CI}}})^{n_{\text{CI}}} + [\text{CI}]^{n_{\text{CI}}}} \cdot \frac{(K_{d_{\text{amRNA}}})^{n_{\text{amRNA}}}}{(K_{d_{\text{amRNA}}})^{n_{\text{amRNA}}} + [\text{antisense-mRNA}]^{n_{\text{amRNA}}} } \right) \notag \\ & - d_{\text{cro}} [\text{cro}] \end{aligned}$$

CII and CIII promote the expression of CI, while cro inhibits the expression of CI. Additionally, CI self-promotes at low concentrations and self-inhibits at high concentrations.: $$\begin{aligned} \frac{d[\text{CI}]}{dt} = & \alpha_{\text{PRE}}\left(\beta_{0\text{PRE}}+\frac{(1-\beta_{0\text{PRE}})\left([\text{CII}]^{n_{\text{CI}}}+[\text{CIII}]^{n_{\text{CI}}}\right)}{K_{d_{\text{PRE}}}^{n_{\text{CI}}}+\left([\text{CII}]^{n_{\text{CI}}}+[\text{CIII}]^{n_{\text{CI}}}\right)}\right) + \\ & \alpha_{\text{PRM}} \left( \frac{\beta_{0\text{PRM}} + \frac{(1 - \beta_{0\text{PRM}}) [\text{CI}]^{n_{a\text{CI}}}}{K_{d_{\text{PRMCI}}}^{n_{a\text{CI}}} + [\text{CI}]^{n_{a\text{CI}}}}}{1 + \left(\frac{[\text{cro}]}{K_{d_{\text{cro}}}}\right)^{n_{\text{cro}}}} \right) \times \frac{K_{i\text{CI}}^{n_{i\text{CI}}}}{K_{i\text{CI}}^{n_{i\text{CI}}} + [\text{CI}]^{n_{i\text{CI}}}} - d_{\text{CI}}[\text{CI}] \end{aligned}$$

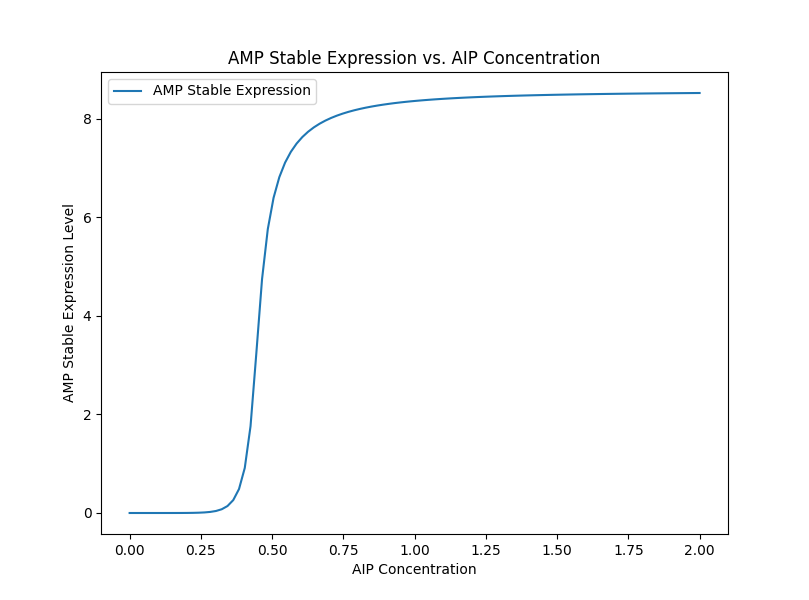

After selecting appropriate parameters and initial conditions, we use the scipy.integrate.solve_ivp function to solve these differential equations. Our system successfully demonstrates the expected behaviors of various substances in the AMP regulatory network, as shown in the figure. Cro, after a brief increase in concentration, is rapidly inhibited by CI and the antisense mRNA chain. Test results with varying AIP concentrations show that AIP can effectively induce an AMP response once the threshold is reached, resulting in a relatively stable concentration of synthesized AMP, effectively acting as a concentration threshold switch.。

In microbial communities, the GLV model is used to understand and predict the dynamic interactions among different microorganisms, such as competition, symbiosis, or predation relationships. Based on communication with the Wet Team members, our model is built upon the following experimental data obtained from co-culturing engineered Escherichia coli with various species of fecal microbiota:

OD600 Measurements: Estimating the absolute abundance of microorganisms by measuring the optical density (OD600) of the culture broth. OD600 measurements provide data on the biomass changes over time for both single populations and microbial communities.

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: Analyzing the results of 16S rRNA gene sequencing to obtain the relative abundance of various species in the microbial community. These data provide detailed information about the composition of the community.。

We performed the following parameter estimation:

Linearization: Firstly, linearize the nonlinear equations of the gLV model through the following transformation: $$\frac{d \log(x_i)}{dt} = \mu_i + \sum_{j=1}^{n} \alpha_{ij} x_j$$ where xi is the absolute abundance of the ith species, μi is its intrinsic growth rate, and αij is the interaction coefficient of the ith species with the jth species.

Least Squares Method: Employ bounded linear least squares algorithms to solve for unknown parameters. Specifically, estimate model parameters by minimizing the sum of squared differences between experimental measurements and model predictions. $$\min \sum_{k=1}^{p} (\hat{y}_k - y_k)^2$$ Where p is the number of time points, ŷk is the model’s predicted value at time point k, and yk is the corresponding experimental measurement.

L1 Regularization: To prevent overfitting, introduce an L1 regularization term to penalize non-zero parameter values: $$F_{y} = \sum_{i=1}^{l} \sum_{j=1}^{m} \frac{1}{p} \sum_{k=1}^{p} (\hat{y}_{k} - y_{k})^2 + \lambda|\Theta|$$ Where l and m represent the number of species in the community dataset and the number of species in each community, respectively. λ is the regularization coefficient, and Θ is the parameter vector. Suppose we have a microbial community study involving four microbes: A, B, C, and D. We measure at time points t1, t2, …, tp to estimate parameters of the Generalized Lotka-Volterra (GLV) model. The absolute abundances of microbes A, B, C, and D are represented as xA, xB, xC, xD. Next, we’ll illustrate how to construct the GLV model and perform parameter estimation based on experimental data.

For ease of parameter estimation, the dynamic equations of the GLV model, after linearization, are as follows:

$$\frac{d \log(x_i)}{dt} = \mu_i + \alpha_{iA} x_A + \alpha_{iB} x_B + \alpha_{iC} x_C + \alpha_{iD} x_D, \quad i \in \{A, B, C, D\}$$

To estimate model parameters, we will use the least squares method to minimize the difference between model predictions and experimental data. Specifically, we seek a parameter set {μi, αij} that minimizes the sum of squared errors between predicted values and measured values at all time points tk:

$$\min \sum_{k=1}^{p} \sum_{i \in \{A, B, C, D\}} (\hat{y}_{ik} - y_{ik})^2$$

Where ŷik is the model’s predicted value for microbe i at time point tk, and yik is the corresponding measured value.

To control model complexity and prevent overfitting, we introduce an L1 regularization term:

$$F = \sum_{k=1}^{p} \sum_{i \in \{A, B, C, D\}} (\hat{y}_{ik} - y_{ik})^2 + \lambda \sum_{i \in \{A, B, C, D\}} \sum_{j \in \{A, B, C, D\}} |\alpha_{ij}|$$ Here, λ is the regularization parameter used to balance fitting errors and the complexity of the model.

Applying the above theory to our hypothetical study, the specific system of equations for the GLV model is:

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{d \log(x_A)}{dt} &= \mu_A + \alpha_{AA} x_A + \alpha_{AB} x_B + \alpha_{AC} x_C + \alpha_{AD} x_D, \\ \frac{d \log(x_B)}{dt} &= \mu_B + \alpha_{BA} x_A + \alpha_{BB} x_B + \alpha_{BC} x_C + \alpha_{BD} x_D, \\ \frac{d \log(x_C)}{dt} &= \mu_C + \alpha_{CA} x_A + \alpha_{CB} x_B + \alpha_{CC} x_C + \alpha_{CD} x_D, \\ \frac{d \log(x_D)}{dt} &= \mu_D + \alpha_{DA} x_A + \alpha_{DB} x_B + \alpha_{DC} x_C + \alpha_{DD} x_D. \end{aligned}$$

By solving this system of equations, we can estimate the growth rates μi and interaction coefficients αij of various microorganisms, thereby gaining deeper insights into the dynamic interactions within the community.

The diffusion process is a natural phenomenon that describes the movement of substances from areas of high concentration to areas of low concentration. Mathematically, this process can be described by the diffusion equation, which is a type of partial differential equation (PDE). For a given substance, the change in concentration C(x,t) over time t and position x can be represented by the following equation:

$$\frac{\partial C}{\partial t} = D \nabla^2 C$$

Where D is the diffusion coefficient, representing the rate of substance diffusion, and ∇2 is the Laplacian operator, used to describe the diffusion effects in space.

In this section, a series of equations are designed to describe the process of the fourth strain (Escherichia coli) releasing AHL signaling molecules, triggering quorum sensing-mediated suicide effects when AHL concentration reaches a specific threshold, and the impact of autoinducing peptide (AIP) released by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (the third strain) on the secretion of antimicrobial peptides (AMP) by Escherichia coli. Pseudomonas aeruginosa releases AIP through quorum sensing, while Escherichia coli increases AMP secretion under the action of AIP, and AMP further damages Pseudomonas aeruginosa through quorum sensing.

The dynamic changes of the signaling molecule AHL in the system are described by the following equation: $$\frac{\partial C(x, y, t)}{\partial t} = \alpha \rho_{4} + D_{s} \nabla^2 C - k_{b}(\rho_{4}) C - k_{e} C$$

Where:

C(x,y,t) represents the concentration of the AHL signaling molecule at time t and in the two-dimensional spatial position (x,y).

α is the rate constant for the release of AHL by a unit of Escherichia coli.

ρ4 is the density of the fourth strain (Escherichia coli), which may have a non-uniform distribution in the two-dimensional space.

Ds is the diffusion constant of AHL in the medium, representing the diffusion capability of the signaling molecule in two-dimensional space.

kb(ρ4) represents the biological degradation rate of AHL by Escherichia coli in the two-dimensional environment.

ke is the chemical degradation rate of AHL in the environment, considering the influence of chemical degradation in two-dimensional space.

Considering the dynamics of the AHL signaling molecule in a two-dimensional environment allows for a more accurate simulation of the signaling transmission process within the Escherichia coli community and the spatial distribution of AHL concentration. This is crucial for understanding and predicting behavioral patterns in microbial communities and how signaling molecules regulate quorum sensing mechanisms of microorganisms in complex environments.

In this model, we further introduce the dynamics of autoinducing

peptide (AIP) released by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (the third strain) and

its impact on the secretion of antimicrobial peptides (AMP) by

Escherichia coli. Pseudomonas aeruginosa releases AIP through quorum

sensing, while Escherichia coli increases AMP secretion under the

influence of AIP, and AMP further damages Pseudomonas aeruginosa through

quorum sensing. The following equations detail this process.

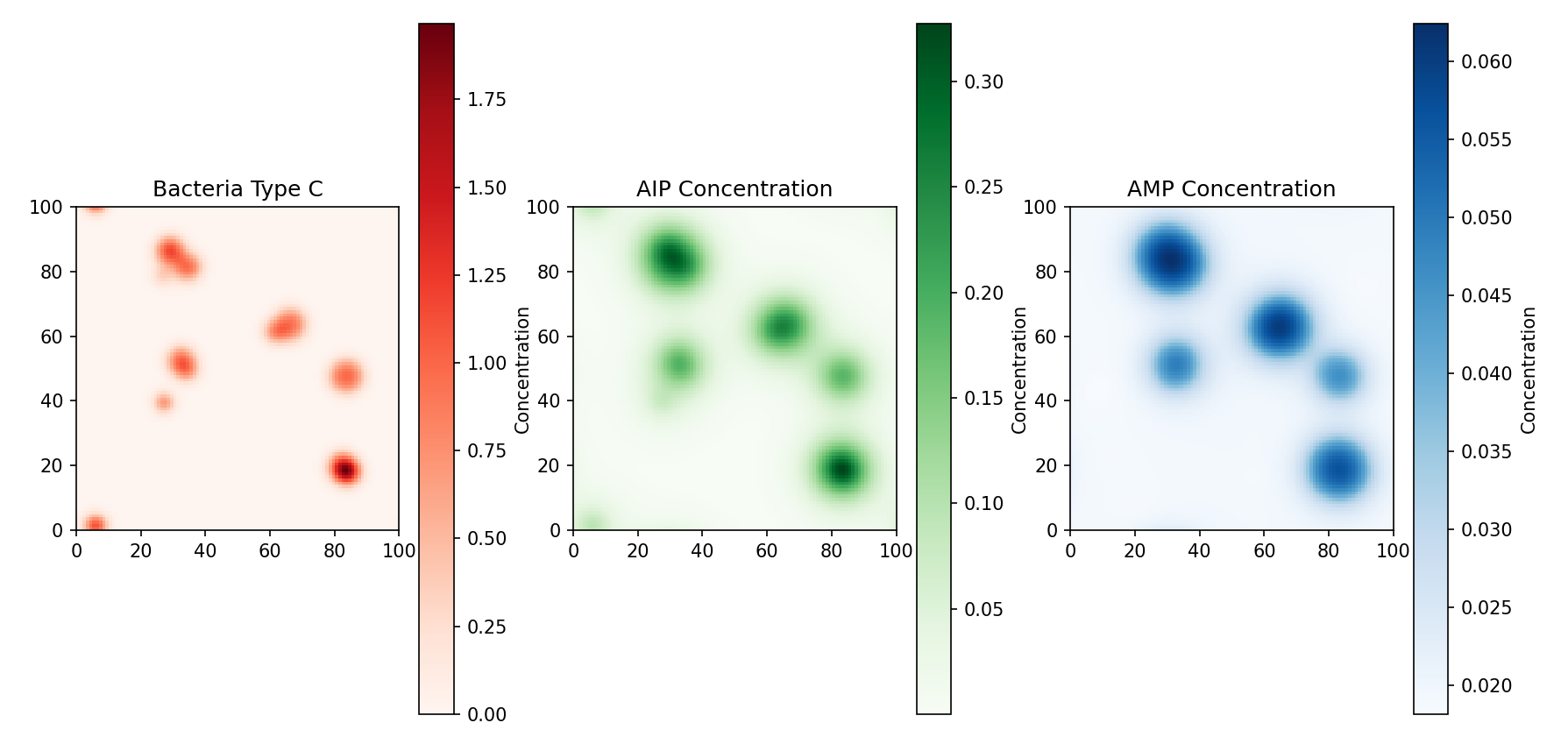

The figure below visualizes the density of Staphylococcus aureus and the

concentrations of AIP and AMP after a period of time in our

simulation.

The dynamics of AIP released by Pseudomonas aeruginosa can be described by the following equation: $$\frac{\partial A}{\partial t} = \beta \rho_{3} + D_{A} \left( \frac{\partial^{2} A}{\partial x^{2}} + \frac{\partial^{2} A}{\partial y^{2}} \right) - k_{a}(\rho_{4}) A - k_{A} A$$ Where:

A(x,y,t) represents the concentration of AIP at the two-dimensional spatial location (x,y) at time t.

β is the rate constant for the release of AIP by a unit of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

ρ3 and ρ4 are the densities of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli, respectively.

ka is the degradation rate of AIP by Escherichia coli.

DA is the diffusion coefficient of AIP in the medium.

kA is the degradation rate of AIP in the environment.

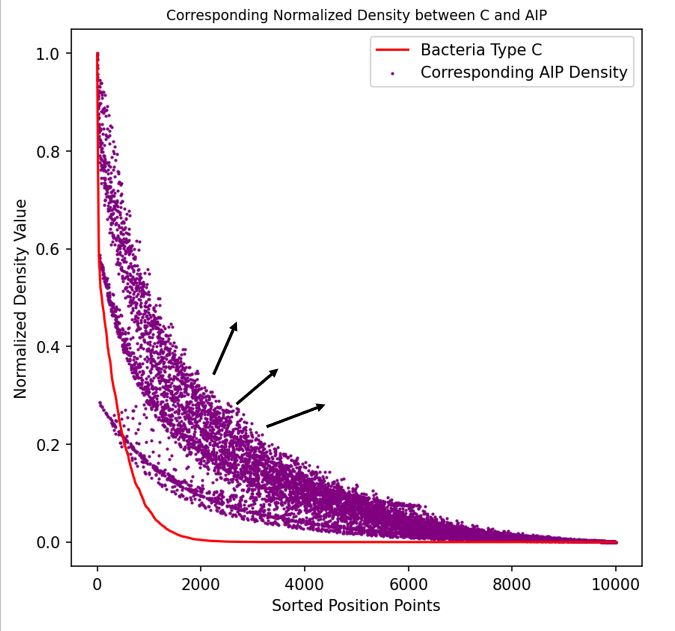

As shown in the figure, we sorted all data points of Pseudomonas aeruginosa after a period of simulation by density from high to low, and normalized the corresponding AIP concentrations of these points. The scatter plot illustrates the correlation between the two, and the arrows in the figure indicate the trend of AIP concentration diffusion.

According to the modeling results in the first part, the secretion rate of AMP by Escherichia coli is determined by the concentration of AIP. We assume that this relationship follows a switch function, where the secretion rate of AMP jumps to its maximum value when the AIP concentration reaches or exceeds a certain threshold, otherwise, the secretion rate of AMP remains zero. This can be simulated by the following equation describing the bactericidal effect of AMP on Pseudomonas aeruginosa: $$\frac{\partial M}{\partial t} = f(A) \cdot \rho_{4} + D_{M} \left( \frac{\partial^{2} M}{\partial x^{2}} + \frac{\partial^{2} M}{\partial y^{2}} \right) - k_{m} \cdot \rho_{3} \cdot M - k_{M} \cdot M$$ Where the secretion rate function f(A) is defined as: $$f(A) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } A < A_{\text{threshold}} \\ R_{\text{max}} & \text{if } A \geq A_{\text{threshold}} \end{cases}$$ Where:

M(x,y,t) represents the concentration of AMP at time t and two-dimensional spatial position (x,y).

A denotes the concentration of AIP.

Athreshold is the threshold AIP concentration triggering AMP secretion.

Rmax is the maximum secretion rate of AMP.

ρ3 and ρ4 represent the densities of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli, respectively.

km is the degradation rate of AMP by Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

DM is the diffusion constant of AMP in the medium.

kM is the natural degradation rate of AMP in the environment.

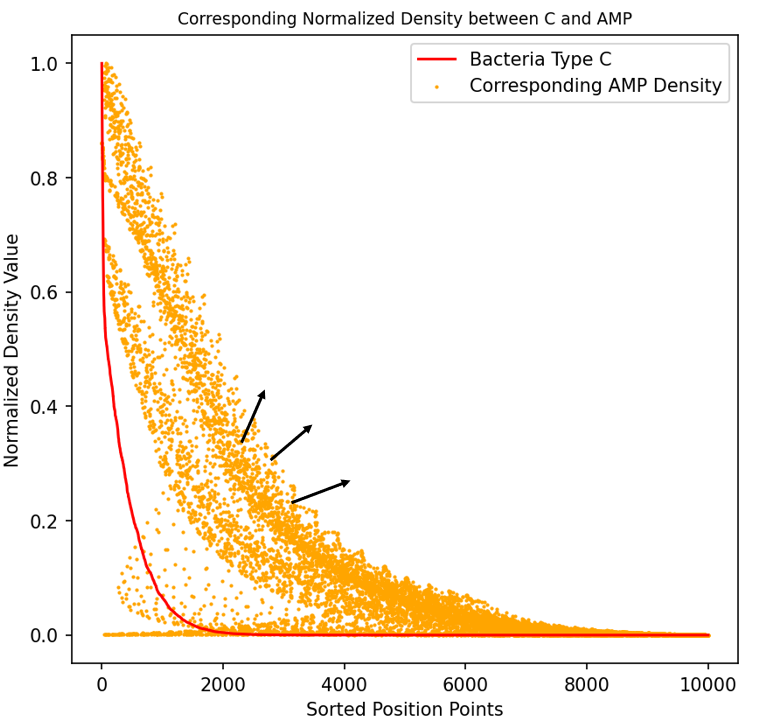

Similar to AIP, we also sorted all data points of Pseudomonas aeruginosa after a period of simulation from high to low density and plotted the corresponding AMP concentrations as scatter points on the graph. Similarly, the correlation between the two and the trend of AMP concentration diffusion can be observed. This result indicates that our system functions well in response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, as the concentration of Escherichia coli is not correlated with that of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, whereas the secreted AMP products exhibit a high correlation.

The classical Generalized Lotka-Volterra (GLV) model has been extended to account for spatial effects and environmental heterogeneity. This extension allows the model to not only describe interactions within populations, such as competition, predation, and symbiosis, but also consider the diffusion behavior of individuals in space. The extended GLV model can be represented as:

$$\frac{\partial \rho_i}{\partial t} = D_i \nabla^2 \rho_i + \rho_i \left( r_i + \sum_{j=1}^{n} \alpha_{ij} \rho_j \right)$$

Where:

ρi(x,y,t) represents the density of the ith bacteria species at time t and spatial position (x,y).

Di is the diffusion coefficient of the ith bacteria species, representing its ability to diffuse in space.

∇2 is the Laplace operator, used to describe the spatial distribution of bacterial density.

ri is the intrinsic growth rate of the ith bacteria species.

αij is the coefficient describing the interaction between the ith and jth bacteria species, with positive values indicating symbiosis and negative values indicating competition or predation.

In this model, the growth rate of each bacteria species is influenced not only by its intrinsic biological characteristics but also by interactions with other bacterial populations. Additionally, the spatial diffusion capability of bacteria allows them to move and expand in the environment, which is crucial for understanding and predicting the spatial structure and dynamic changes of microbial communities.。

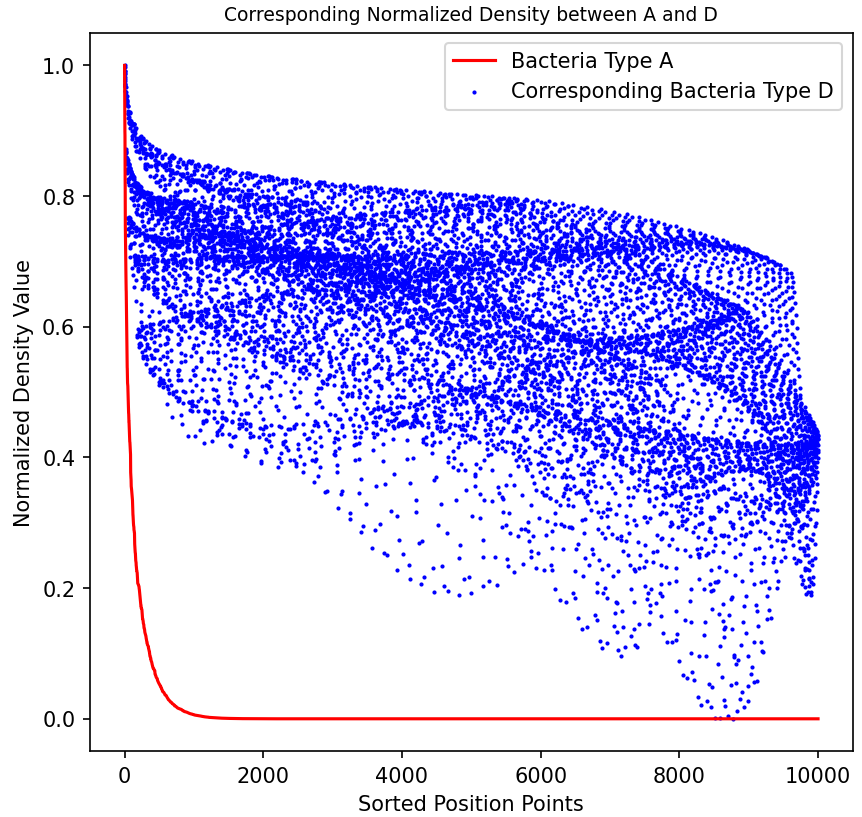

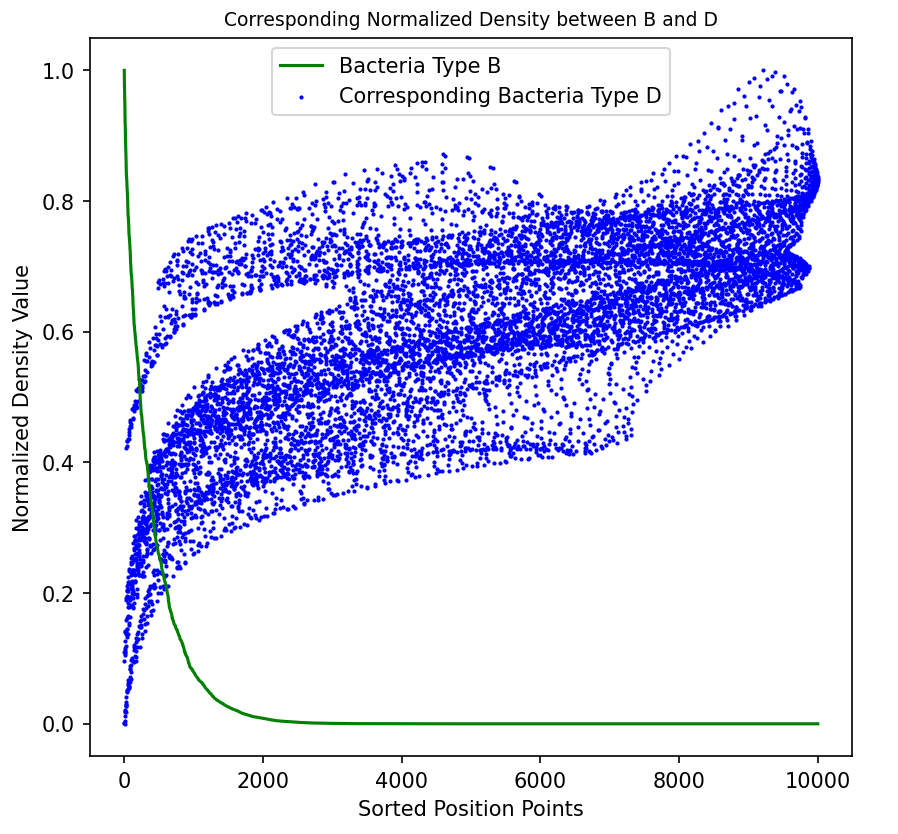

As shown in the figure, we assume a symbiotic relationship between bacteria of type A and type D (engineered Escherichia coli), while type B and type D exhibit an antagonistic relationship. We sorted all data points of bacteria types A and B by density from high to low after simulating for a period of time, and plotted the corresponding points of bacteria type D as well. The figure clearly shows the correlation between them, indicating that bacteria type D tends to grow in areas where bacteria type A is present but bacteria type B is absent.

Significant extensions have been made to the Generalized Lotka-Volterra (GLV) model to account for environmental carrying capacity and nutrient limitation. These extensions consider two key ecological mechanisms of bacterial population growth: logistic growth rate due to environmental carrying capacity and Monod equation under nutrient limitation.

Environmental carrying capacity refers to the maximum stable size of a biological population that the environment can sustain. Beyond this size, environmental resources are insufficient to support the survival of additional individuals, leading to a decrease in population growth rate. This effect is described in the logistic growth model, which is represented by the following equation:

$$\frac{dN}{dt} = rN\left(1 - \frac{N}{K}\right)$$

Where N is the population size, r is the maximum growth rate, and K is the carrying capacity. As N approaches K, the growth rate decreases, simulating the slowdown in population growth due to resource limitation.

Nutrient limitation dynamics can be described by the Monod equation, a core concept in microbial growth models used to depict the relationship between microbial growth rate and nutrient concentration:

$$\mu = \mu_{\max}\frac{[S]}{K_s + [S]}$$

Where μ is the growth rate, μmax is the maximum growth rate, [S] is the nutrient concentration, and Ks is the half-saturation constant, representing the nutrient concentration at which the growth rate is μmax/2.

By integrating these two concepts, the GLV model can be extended to a complete equation that considers spatial distribution, environmental carrying capacity, and nutrient limitation.

$$\frac{\partial \rho_i}{\partial t} = D_i \nabla^2 \rho_i + \rho_i \mu_i \left(\frac{[S]}{K_s + [S]}\right)\left(1 - \frac{\rho_i}{K_i}\right) + \sum_{j=1}^{n} \alpha_{ij} \rho_j$$

$$\frac{\partial [S]}{\partial t} = D_s \nabla^2 [S] - \sum_{i=1}^{n} \eta_i \rho_i \frac{[S]}{K_s + [S]}$$

Here, ρi(x,y,t) and [S](x,y,t) respectively represent the density of the ith bacteria species and the concentration of nutrient at time t and spatial location (x,y). Di and Ds are the diffusion coefficients of bacteria and nutrient, while ηi is the conversion rate of nutrient consumed by the ith bacteria species.

In this way, the extended GLV model not only simulates interactions within populations and spatial diffusion behavior but also accurately describes how nutrients affect the growth and distribution of microbial communities, providing powerful theoretical tools for our project implementation.

In microbial engineering, distinguishing between free-living and colonized bacteria is crucial for understanding and optimizing the spatial structure and functionality of microbial communities. Free-living bacteria (ρf) refer to bacteria that are not fixed to specific surfaces or interfaces, while colonized bacteria (ρs) are bacteria that have formed stable colonies on biological or non-biological surfaces. The following equations describe the dynamic changes of these two states of bacteria in the environment, particularly considering the adhesion process of free-living bacteria transitioning to colonized bacteria.

The dynamic changes of free-living bacteria can be described by the following equation: $$\frac{\partial \rho_{f}}{\partial t} = D_f \nabla^2 \rho_{f} + \rho_{f} \left( \mu_f \left(\frac{n}{n + K_s}\right) \left(1 - \frac{\rho_{f} + \rho_{s}}{K}\right) + \sum_{j=1}^{3} \alpha_{fj} \rho_j \right) - a \rho_{f}$$ Where Df represents the diffusion coefficient of free-living bacteria, μf is the intrinsic growth rate of free-living bacteria, n is the concentration of nutrient, Ks is the half-saturation constant, K is the environmental carrying capacity, αfj is the coefficient of interaction between free-living bacteria and other colonies, and a is the conversion rate of free-living bacteria adhering to become colonized bacteria.

The dynamic changes of colonized bacteria can be described by the following equation: $$\frac{\partial \rho_{s}}{\partial t} = \rho_{s} \left( \mu_s \left(\frac{n}{n + K_s}\right) \left(1 - \frac{\rho_{f} + \rho_{s}}{K}\right) + \sum_{j=1}^{3} \alpha_{sj} \rho_j \right) + a \rho_{f}$$ Here, μs represents the intrinsic growth rate of colonized bacteria, and αsj is the coefficient of interaction between colonized bacteria and other microbial populations. This equation not only reflects the increase of colonized bacteria through their own growth and interaction but also acquires new individuals through the adhesion process of free bacteria.

During the formation of biofilms, the accumulation of extracellular polysaccharides (s) is one of the key steps and can be described by the following equation: $$\frac{\partial s}{\partial t} = D_s \nabla^2 s + p \rho_{s} - d s$$ Here, Ds is the diffusion coefficient of extracellular polysaccharides, p is the rate at which colonized bacteria produce extracellular polysaccharides, and d is the degradation rate of extracellular polysaccharides.

The formation and accumulation of biofilms have a significant impact

on the diffusion process of nutrients. In biofilms, nutrient diffusion

is no longer a simple free diffusion process but is influenced by the

complex structure of the biofilm. Factors such as the porous structure,

viscosity, and composition of the biofilm can affect the rate of

nutrient diffusion. Therefore, to more accurately simulate the dynamic

changes of nutrients in the biofilm environment, we need to modify the

diffusion dynamics equation of nutrients accordingly.

The diffusion of nutrients in biofilms can be considered as a diffusion

process in a heterogeneous medium. In this environment, the effective

diffusion coefficient of nutrients is typically lower than that in free

solution because the physical structure of the biofilm impedes the

movement of nutrients. Additionally, the microenvironment within the

biofilm may further promote or inhibit the consumption of specific

nutrients, thereby affecting the distribution and concentration gradient

of nutrients.

Considering the influence of biofilm on nutrient diffusion, we can modify the diffusion dynamics equation for nutrients as follows: $$\frac{\partial n}{\partial t} = \nabla \cdot (D_n(s) \nabla n) - \sum_{i=1}^{n} \eta_i \rho_i \frac{n}{K_s + n} + r$$ Where,

n(x,y,t) represents the concentration of nutrients.

Dn(s) is the effective diffusion coefficient of nutrients in the biofilm, which is a function of the concentration of extracellular polymeric substances s, reflecting the influence of the biofilm on nutrient diffusion.

∇ ⋅ (Dn(s)∇n) represents the diffusion term of nutrients considering the influence of the biofilm.

ηi is the conversion rate of nutrient consumption by the ith type of bacteria.

Ks is the half-saturation constant, indicating the concentration of nutrients at which the consumption rate reaches half of its maximum value.

r represents the rate of nutrient production or input.

The influence of extracellular polymeric substance concentration s on the effective diffusion coefficient Dn(s) of nutrients needs to be validated through wet experiments. Typically, as the concentration of extracellular polymeric substances in the biofilm increases, the effective diffusion coefficient decreases. We make the assumption here: Dn(s) = Dn0exp (−αs) Where Dn0 is the free diffusion coefficient of nutrients under no biofilm conditions, and α is a positive constant describing the extent to which extracellular polymeric substance concentration affects the diffusion coefficient.

In this way, we can more accurately simulate the distribution and dynamic changes of nutrients during the formation and development of biofilms, providing a theoretical basis for understanding and controlling biofilm-related processes.

The figure below shows the simulation of the change in nutrient

concentration over time, considering both the growth of the biofilm and

the consumption by bacterial colonies.

Based on our previous discussions, we need to consider the molecular dynamics of AIP, AMP, AHL, and other molecules on bacterial growth and diffusion.

To describe the suicidal effect triggered when the AHL concentration reaches a specific threshold, we introduce a switch function S(C) to represent the activation condition for the suicidal effect: $$S(C) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{If } C < C_{\text{threshold}} \\ 1 & \text{If } C \geq C_{\text{threshold}} \end{cases}$$ Here, Cthreshold is the AHL concentration threshold required to trigger the suicidal effect. When the AHL concentration reaches or exceeds this threshold, Escherichia coli initiates the suicidal program.

To reflect the influence of the suicidal effect on Escherichia coli density, the Escherichia coli density equation adds terms related to S(C): $$\frac{\partial \rho_4}{\partial t} = D_4 \nabla^2 \rho_4 + \rho_4 \left( \mu_4 \left(\frac{n}{n + K_s}\right) \left(1 - \frac{\rho_4}{K_4}\right) + \sum_{j=1}^{3} \alpha_{4j} \rho_j \right) - a(\rho_4, s) \rho_4 + m(\rho_4, s) - \delta S(C) \rho_4$$ Where,δ describes the intensity of the suicidal effect.

To reflect the killing effect of antimicrobial peptides (AMP) on Staphylococcus aureus (the third bacterial strain), we update the density variation equation for Staphylococcus aureus to incorporate the effect of AMP. The killing effect of AMP is represented by a degradation term proportional to the AMP concentration M, which directly affects the survival rate and density variation of Staphylococcus aureus:

$$\frac{\partial \rho_{3}}{\partial t} = D_{3} \nabla^2 \rho_{3} + \rho_{3} \left( \mu_{3} \left(\frac{n}{n + K_{s3}}\right) \left(1 - \frac{\rho_{3}}{K_{3}}\right) + \sum_{j \neq 3} \alpha_{3j} \rho_{j} \right) - \gamma(M) \rho_{3}$$

Where:

ρ3(x,y,t) represents the density of Staphylococcus aureus at time t and two-dimensional spatial position (x,y).

D3 is the diffusion coefficient of Staphylococcus aureus in the medium, indicating the ability of Staphylococcus aureus to move in two-dimensional space.

μ3 is the maximum intrinsic growth rate of Staphylococcus aureus under conditions of sufficient nutrients.

K3 is the environmental carrying capacity of Staphylococcus aureus.

Ks3 is the half-saturation constant of Staphylococcus aureus growth response to nutrients.

α3j represents the interaction coefficient between Staphylococcus aureus and other bacterial strains j.

γ(M) is a function describing the killing effect of AMP concentration M on Staphylococcus aureus, reflecting that a higher AMP concentration results in a stronger killing effect on Staphylococcus aureus.

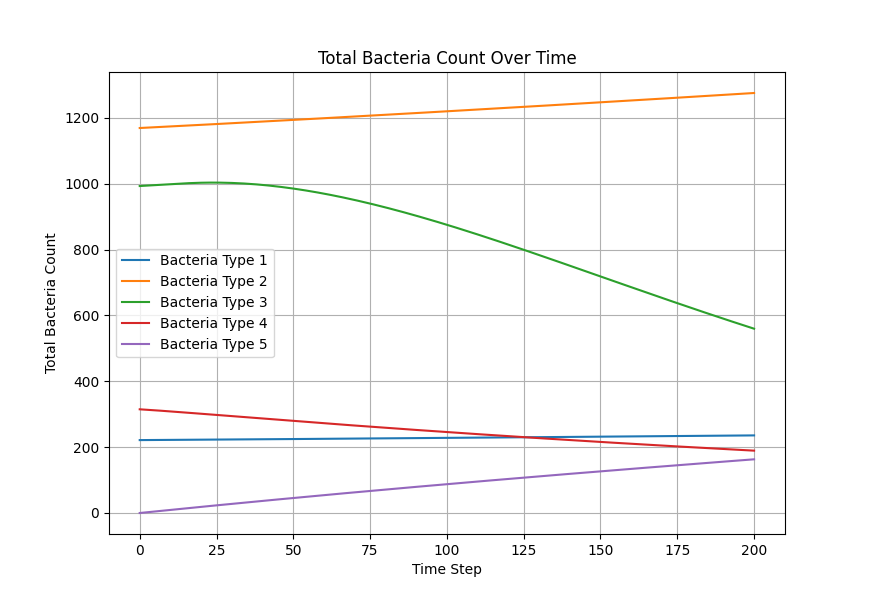

As shown in the figure, we statistically count the total numbers of various bacteria in the simulation, where Bacteria Type 3 represents Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacteria Type 4 and 5 are free and settled Escherichia coli, respectively. It can be seen that our engineered bacteria have a significant inhibitory effect.

In this study, we implemented a complex dynamic simulation model of microbial communities aimed at exploring the interactions between different bacterial species, particularly the colonization process of engineered Escherichia coli and its symbiotic and antagonistic relationships with other bacterial populations. The model implementation is based on the Python programming language and utilizes numerical methods to solve a series of partial differential equations to simulate bacterial spatial diffusion, growth kinetics, and interactions.

The dynamic changes of bacterial populations in the model are described using an extended Generalized Lotka-Volterra (GLV) model, which includes both the freely moving state (ρf) and the settled state (ρs) of bacteria, as well as the transition process between them. Additionally, the consumption of nutrients and the production, diffusion, and degradation of signaling molecules (such as AHL, AIP, and AMP) are considered, which collectively influence the growth and interactions of bacterial populations.

The key implementation steps of the model include:

1. Using the generate_colony_density_fixed_max

function to randomly generate the initial distribution of bacterial

population density according to a two-dimensional normal distribution

based on the given center position, radius, and maximum density.

2. Initializing a spatial grid to simulate the distribution of bacterial

populations and nutrients in two-dimensional space.

3. Defining parameters such as diffusion coefficients, growth rates,

interaction coefficients of bacterial populations, and nutrients, which

directly affect the dynamic behavior of the model.

4. Using the update_states

function to update bacterial density and nutrient concentration at each

time step, including calculating bacterial diffusion, growth, and

interactions, as well as the dynamic changes of signaling

molecules.

5. Visualizing the dynamic behavior of the model using visualization

tools, including the spatial distribution of different bacterial species

and changes in nutrient concentration.

Model testing shows that through numerical simulation, we can observe symbiotic relationships between the first bacterial species and the fourth bacterial species (Escherichia coli), as well as antagonistic relationships between the second bacterial species and Escherichia coli. Meanwhile, the model successfully simulates the behavior of settled Escherichia coli (the fifth bacterial species), with interaction parameters consistent with those of free Escherichia coli. Furthermore, the model also considers the influence of biofilm formation on nutrient diffusion, further increasing the biological significance and practical value of the model.

Through this implementation, we not only validate the theoretical foundation of the model but also provide a powerful tool for further research on the spatial dynamics of microbial communities, especially in exploring microbial interactions and biofilm formation processes.

Below are our simulation results: